The design honors the enduring legacy of Modernist ideas and their impact on architecture.

It embraces the pioneering spirit of the mid-century modern buildings that have shaped Lincoln since Walter Gropius made the town his home in 1938. The original 1948 school was designed by Lincoln resident Lawrence B. Anderson.

By retaining the gable roofs, the renovation pays homage to the architects’ original intent.

Transparent views from front to back continue the Modernist onus on daylighting and connection to nature.

Architectural Forum Magazine, 1950

Historically a rural farming community, the Town of Lincoln became a beacon for Modernist architecture after Gropius’ arrival.

“Our community is closely tied to the Modernist architect movement,” says Buck Creel, former Lincoln School Administrator. “We wanted to retain those principles knowing that replicating it exactly was not the right thing to do for a modern school building.”

1953

Now

Striking a balance between old and new, the design introduces next generation learning spaces including a learning commons, media center, and grade-level learning neighborhoods.

It also retains the original building’s orientation and single-story, L-shaped format—in turn preserving the town’s historic baseball field, home to a beloved semi-professional team from 1932—as well as its distinctive gabled roofs.

Most classrooms open directly to the outside and offer views of woodlands, meadows, streams, or wetlands.

Passionate about sustainability, the Lincoln community pushed for a fully net zero renovation.

The net zero energy design reduces the building’s ecological footprint and serves as an educational tool for students, staff, and parents.

Key Sustainability Stats for the Lincoln School

|| Carbon Reduction | 48.1% |

| Payback | 3.5yrs |

| EUI | <25 kBtu/SF/yr |

| 100 % Solar PV roof and parking canopies (PPA) | 1.4 MV |

| Energy Storage (PPA) | 600 kW |

“As teachers, we’re thinking ahead for ways to connect the net-zero component to our projects about the environment,” says Matt Reed, 4th Grade Teacher. “We want kids to think about how they might go into the world, thinking about ideas like sustainability.”

48.1%

Carbon Reduction

3.5

years

Payback

23.9

kBtu/sf

EUI

“Being a net zero building was a core value for this community. It’s not just about reducing costs, but doing what’s right for the environment and for a community that values open space and conservation.”

Becky McFall, Former Superintendent

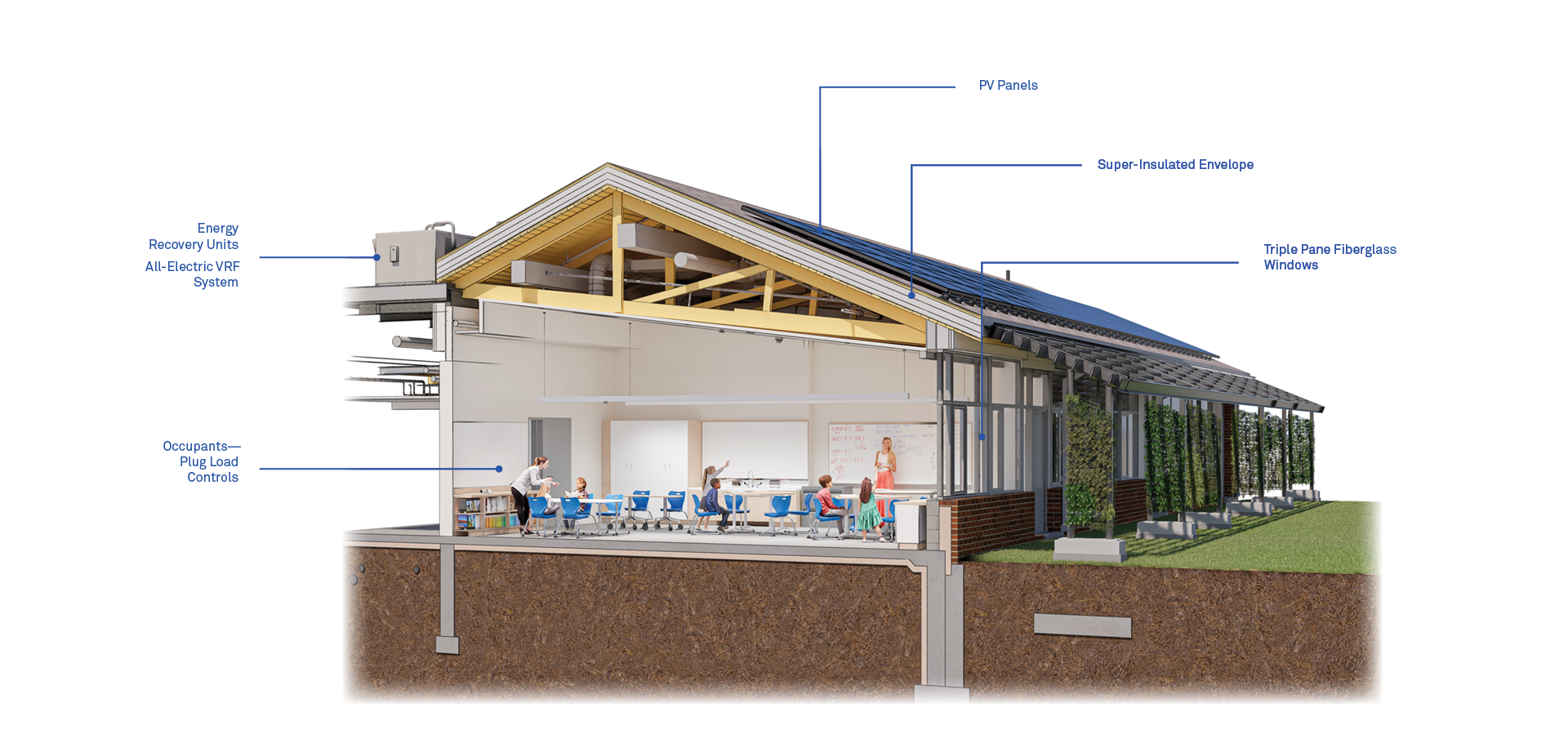

The net zero goal was achieved through a series of careful design choices.

- Painstaking façade work that involved stripping off all brick before adding wider foundations to create deeper insulation

- Harvesting 100% of the school’s energy onsite using rooftop solar panels and parking canopies

- Designing all-electric MEP systems in every part of the school

- Use of several sustainability features found in the original Modernist building, including sun shading devices and passive solar heating and cooling

The design reimagines the old building’s outdated learning spaces.

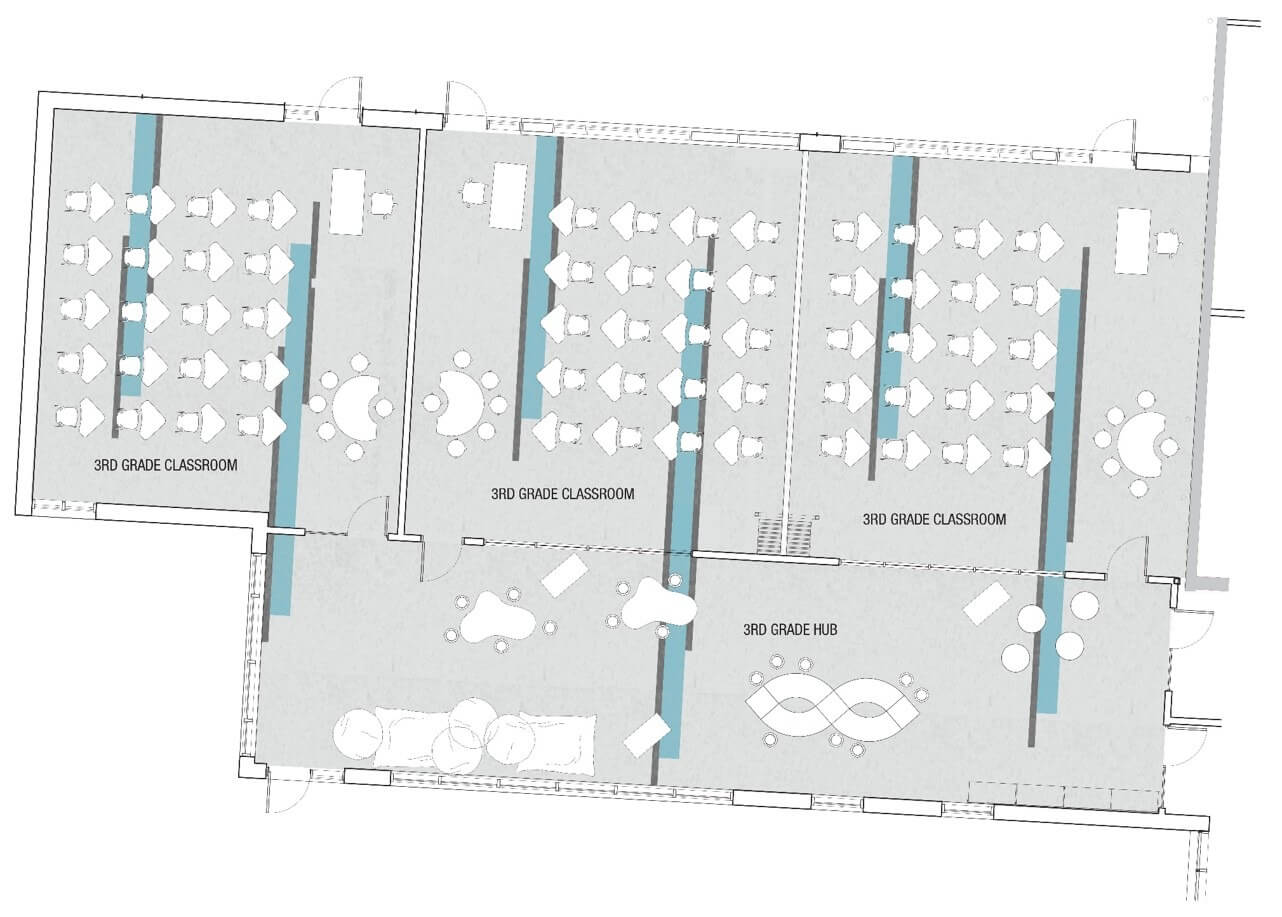

The new environment aligns with current understanding of how children learn. The school’s layout is defined by grade-level neighborhoods, or “Hubs”, each surrounded by classrooms for grades 3-8, with a single Hub for K-2.

The Lincoln School has a “team teaching” model. Teachers with different subject specialties work in teams of three across 70-80 students in each grade.

The Hubs

|Different students learn best in different ways. The Hubs create flexibility, allowing teachers to bring students out of the classroom and engage in different modalities of learning.

The Hubs encourage teamwork, problem-solving, and creative thinking. Students work together, exchange ideas, and actively participate in hands-on projects. Meanwhile, informal learning spaces dot the widened corridors to provide spontaneous connections outside the classroom.

“We’ve taken these spaces that used to be double-loaded corridors of classrooms and created communities within a school community,” says McFall. “It’s really changed the way teachers work and it’s changed the way kids learn. It’s been amazing to watch that transition and I’m eager to see how it will evolve in years to come.”

Operable walls allow for flexible learning spaces—teachers and students move freely from classroom to Hub and vice versa.

This encourages collaboration while supporting modern learning styles such as project-based learning and personalized instruction.

“My classroom has a glass wall we can open and close. I love that we move in and out of my classroom into the Hub space on a regular basis. And the kids love being able to move out there and work in small groups.”

Matt Reed, 4th Grade Teacher

Conservation and re-use drove much of the design.

Select classrooms feature exposed wood beams salvaged from the old school.

“Here’s a town only 12 miles from downtown Boston, and yet it’s considered rural because of the value we place on open space and conserving land.”

Becky McFall, Former Superintendent

The complex site is bound on all sides by wetlands. Several streams run through the property, including a tributary to Stony Brook Reservoir, a public water supply.

The design protects these natural features while improving connections to the town’s many hiking, cycling, and cross-country ski trails as well as adjacent parks, meadows, playgrounds, sports facilities, and a community center.

The new plaza is a gathering place for students and an important civic space for the community.

The New Plaza

|Using simple materials, the plaza features all-native planting and preserved mature trees and vegetation.

Wood and granite benches come from salvaged trees on site and boulders come from both on site and from the town.

Beyond the plaza, the preserved historic ballfield sits atop a newly designed subsurface infiltration chamber for rainwater storage. Both main parking lots were raised 18 feet to improve positive drainage and allow the capture and treatment of stormwater.

The learning commons hosts events and ceremonies throughout the year.

As the largest public building in Lincoln, the school is the focal point of community life.

A new auditorium welcomes the public for student performances, town meetings, and guest speakers.

The school also serves as Lincoln’s climate emergency shelter. An all-electric kitchen eliminates the need for natural gas fuel systems for heating and cooking.