Designing for military facilities, including highly secure spaces such as SCIFs, requires a special kind of understanding, expertise, and attention to detail.

Unlike conventional projects, military environments demand heightened focus on security and safety measures, ensuring the protection of sensitive information. It is also crucial to emphasize efficiency and flexibility as missions evolve, to streamline processes as space requirements change.

To dive deeper into these complexities and SCIF requirements, we sat down with our Government Market Leader, Jennifer Howe, to discuss the challenges and facets of designing SCIFs along with other innovative environments tailored for our government clients.

Q: Let’s start with the most important question, can you tell us what a SCIF is?

A: The acronym stands for a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility.

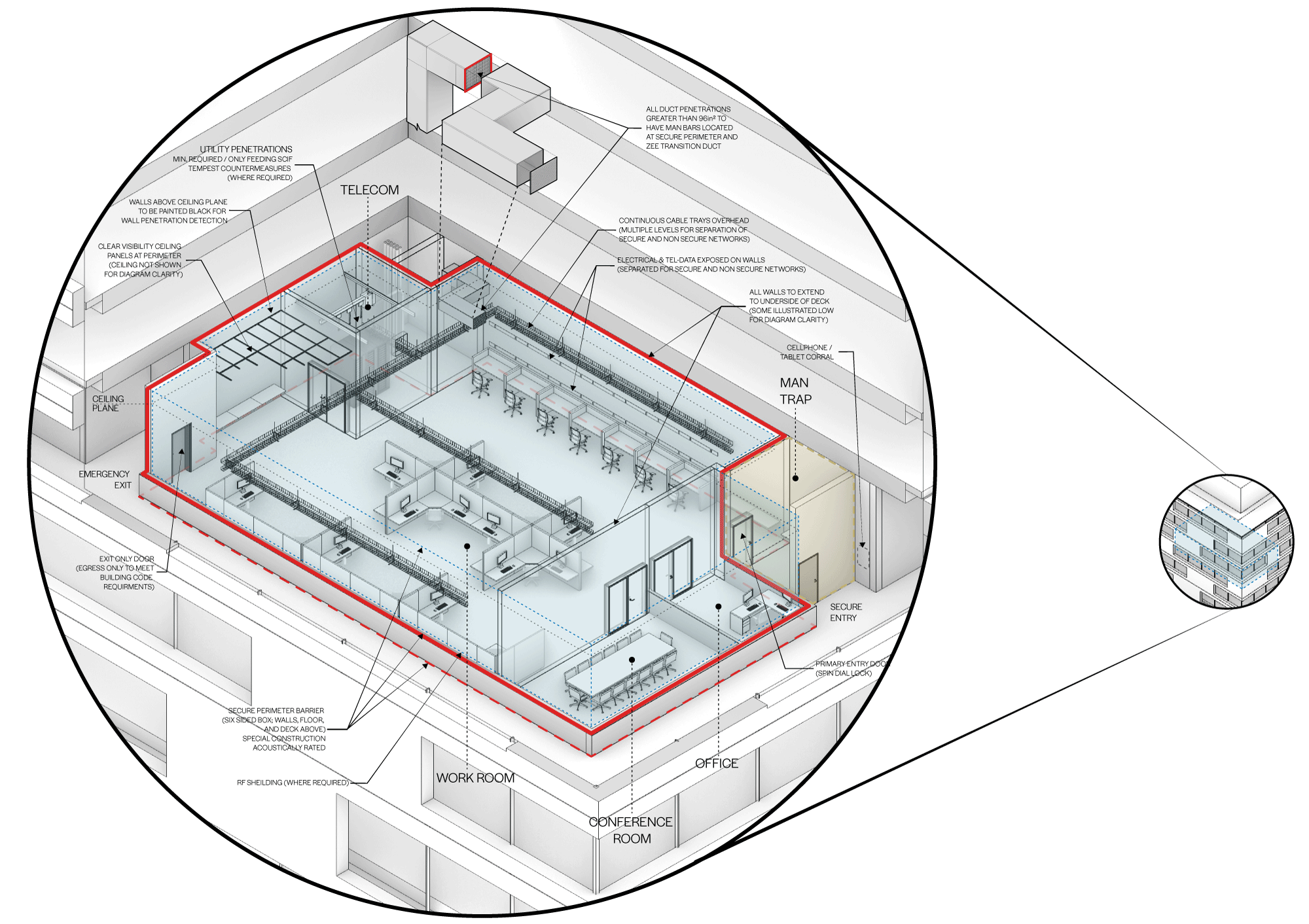

It’s essentially a controlled space with certain protections around it – ensuring that only authorized personnel can enter into the facility, see into the facility, and hear into the designated area. It could be an entire building or just one room. Each SCIF can have a specific group of authorized people. Just because someone is authorized in one SCIF, doesn’t mean they have permissions in another. Similar to our other projects, these spaces are tailored to the needs of the specific users, however, it’s often important to keep the areas as flexible as possible, as missions change and evolve.

SCIFs can be created for a number of purposes. They aren’t just used for office space or meeting rooms; they can also be manufacturing facilities, research facilities, learning and training environments, etc. However, it’s important to remember that the SCIF designation is not about what’s happening inside the space; it's about the envelope surrounding the space.

Various secure space elements requiring design consideration:

Q: What are the necessary requirements to be able to design a SCIF?

A: Well, everyone working on the project must be a United States citizen. And the company hired must be a U.S. company. Those are the basics.

Furthermore, the team working on the project must keep communication and documentation strictly within the team. SMMA has a strict process in place when onboarding team members to these projects, including password protected access to all files to ensure cyber security protocols are maintained.

That just covers the internal process. Physical requirements will be defined on a case-by-case basis, but there are general standards we follow. A security guideline outlines the requirements for the design, construction, and accreditation of SCIFs. If you have a six-sided box – four walls, a floor, and a ceiling – we must ensure its protected properly.

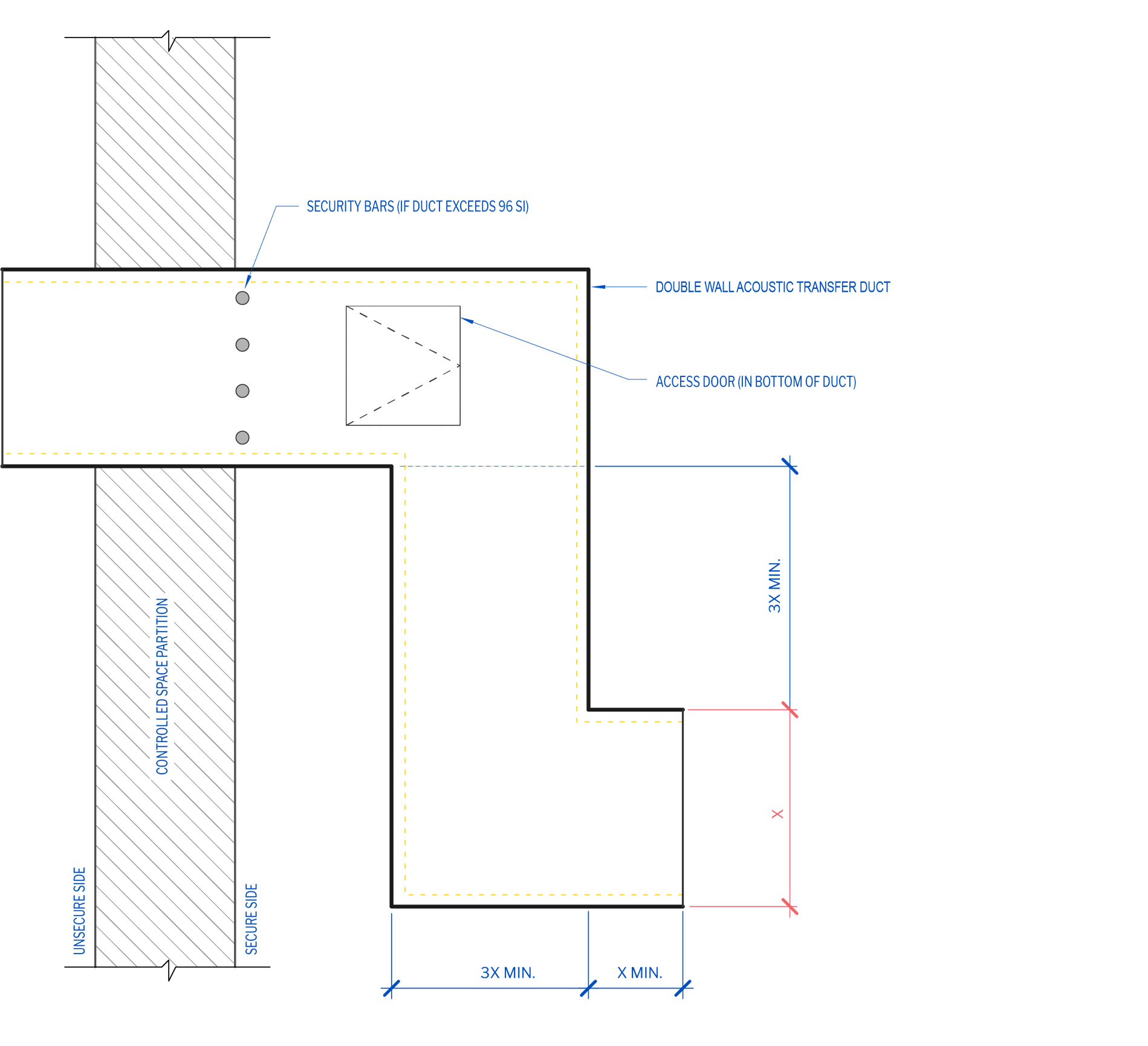

Z-Duct penetration for acoustic separation

For example, if an HVAC duct running through the SCIF perimeter walls is large enough for someone to breach the physical barrier of the SCIF, bars must be installed within the duct to prevent unauthorized access. Additionally, depending on the duct's location, we must assess where sound might travel and determine if sound attenuation is necessary. A strong understanding of acoustics is essential in this process.

Q: What is something your team needs to consider when starting these projects? How do you ensure the process runs smoothly?

A: Project management and a thorough timeline is key. Getting a SCIF up and running takes time and oversight, as many projects do.

Once the SCIF is complete, it must be accredited by a specific group outside the project team. So, sticking to those project milestones is incredibly important; our team is used to the fast-paced requirements. Sometimes, government resources are limited, so our job is to be able to accept whatever curveballs come our way and find solutions to challenging obstacles, all while staying on time and on budget.

We also handle a significant portion of our projects in-house, benefiting from the expertise of many professionals working together under one roof. Our multi-disciplinary approach not only streamlines the process but also serves our clients' best interests by minimizing the need to share information externally.

Q: What is it like designing for missions and objects we are not privy to? How can we best support the users of this space with limited information?

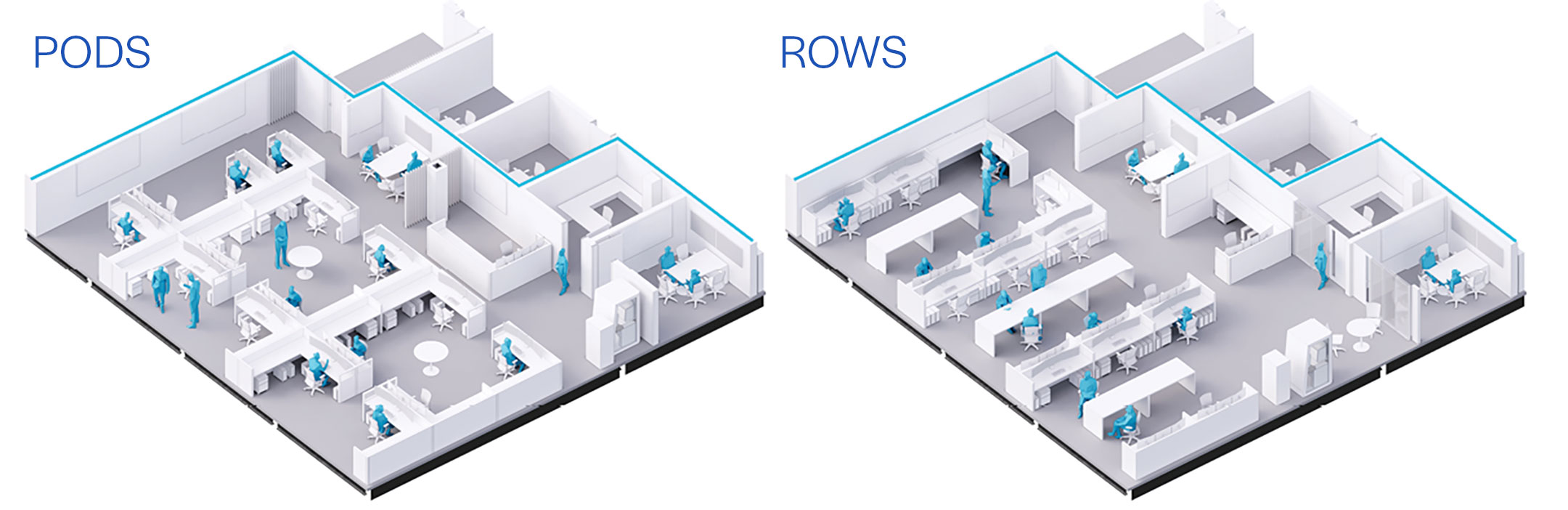

A: We might not know what they are working on, but we can understand how they work so we can best support them.

This involves asking a lot of questions to get the clearest picture we can – questions like, are people working at their desks independently? What does a typical collaborative session look like? What other areas will they need access to quickly and easily? Can everyone within the secure space see what their colleagues are working on? And so on.

Workplace layouts for varying collaboration types in secure spaces:

Q: How do we continue to enhance our designs and our approach for government clients?

A: A huge advantage to working at a multi-disciplinary firm with numerous markets is the wealth of expertise and breadth of experience just within SMMA.

Our government projects definitely look a bit different than some of my colleagues’ projects in other markets – an office renovation in the government practice can differ quite a bit from a renovation in our workplace practice. But our goal is always to put the client first, and there are many examples of workplace trends and efficiencies that can also serve our military. Design concepts like open collaborative workspaces with low wall cubicles may not be traditional in our government clients' past projects, but it’s our job to help them push the norm when it makes sense. It’s critical for design to evolve as our world and our work changes.

Interior view at security desk of secure space. Red screens and glassboard are used to show security risk points for review.

Last, we aim to support the need for flexible design. As I mentioned, these spaces must be accredited upon completion, a process that can sometimes take up to a year. If, after gaining accreditation, the design needs to change a few years later to accommodate a new mission, a renovation would require re-accreditation. To minimize what could be a costly and time-consuming process, we focus on planning ahead, ensuring our designs are adaptable and capable of supporting our clients' needs for as long as possible. As programs grow, they may need additional space but would like to utilize what’s already been built. Using a modular approach can lay the groundwork for future expansion.

Q: Are there any additional ideas you’d like to touch on?

A: I think something we have to consider, even though security is at the forefront of these designs, is user experience.

We wouldn't be fulfilling our responsibilities if we didn't consider the experience of spending long hours in these secure environments. While functionality is the driver for these projects, aesthetic details can significantly influence the mood, focus, and effectiveness of service members and civilians in these spaces. Design elements such as lighting in windowless spaces, paint colors, furniture, and other interior finishes and sensory considerations can greatly enhance the overall user experience.